June 2, 2020

Language history was made in Canada almost 180 years ago, but not everyone agrees on whose history it was.

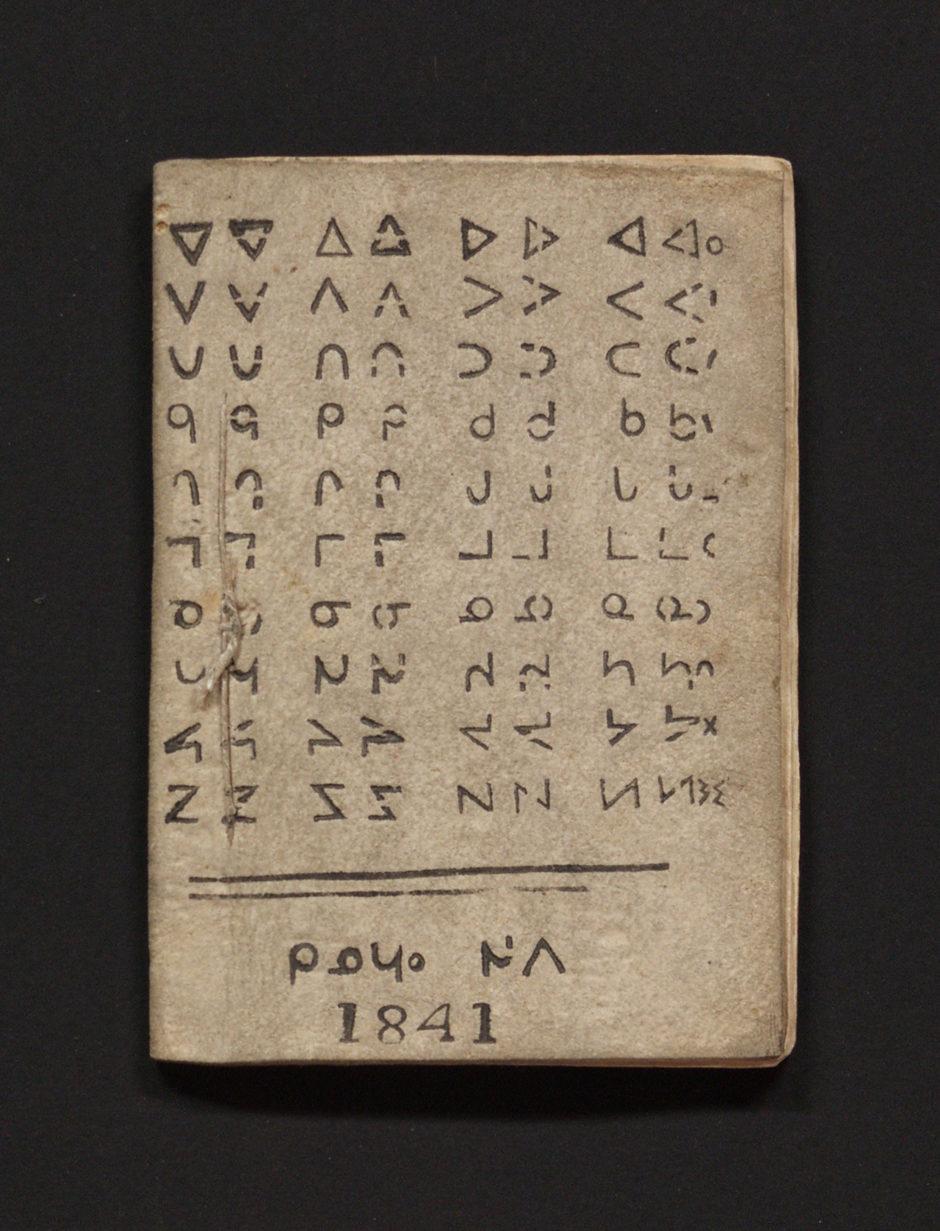

In the northern reaches of what is now Manitoba, at Norway House, a Christian hymn was printed in Cree syllabics — a script alien to the Western eye. The syllabics are a writing system that represents the sounds of spoken Cree in shapes and forms, without analog in Roman lettering.

That was in 1840. Early the next year, a complete booklet of select Christian hymns in Cree was published in the same script. That hymnal consisted of 20 slim pages bound in Western book form — the first booklet printed in Cree syllabics.

But the origin of the writing system is contested. Historians generally did not credit the Cree with inventing the Cree syllabary (the system of Cree syllabics). Credit for that went to James Evans, a Wesleyan Methodist Christian missionary.

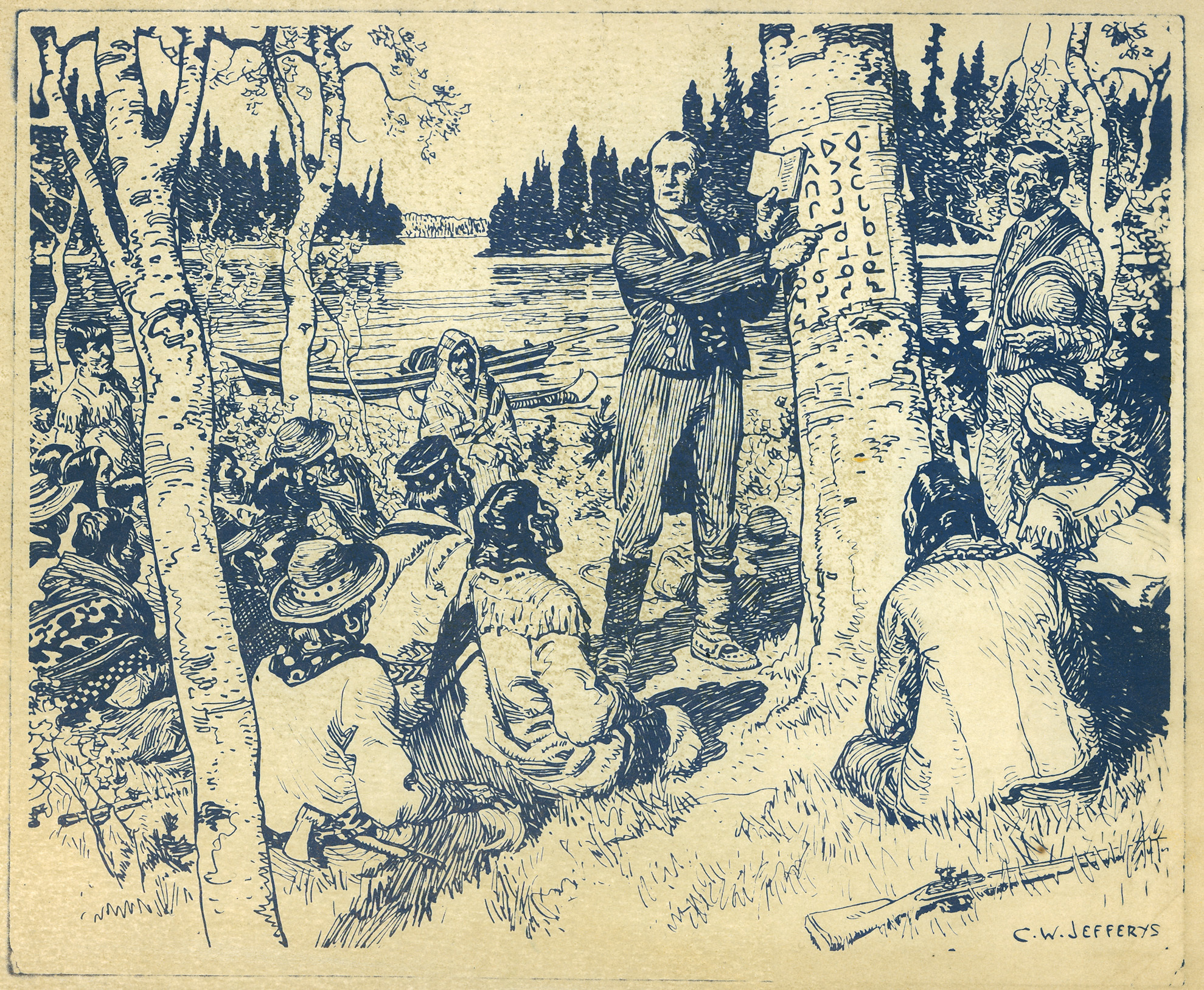

The story goes that Evans invented the syllabary for the Cree.

But the Cree have their own stories of the origin of the syllabary. Those stories have nothing to do with Evans, who appears to have never specifically claimed to have invented the syllabics.

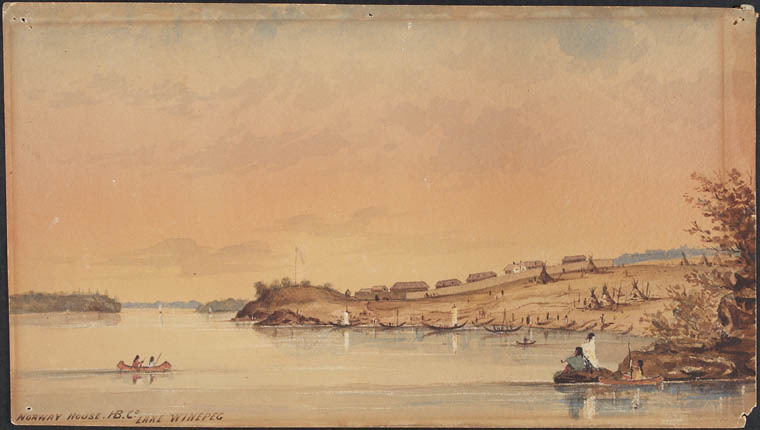

Evans arrived in Norway House, Man., accompanied by the Ojibwe linguists Peter Jacobs (OJ Pahtahsega), Henry Bird Steinhauer (Sowengisik), and others in 1840.

Norway House was a busy place at the time — it was an administrative hub of Rupert’s Land, a trading centre for the Hudson’s Bay Company, and a locus of fur trading routes branching out across western and northern Canada.

Evans went to Norway House as a Christian missionary. The Indigenous men who accompanied him were devout Christians: Jacobs and Steinhauer were both later ordained as ministers. Evans was an accomplished linguist who had worked with Indigenous communities in Ontario before going to Norway House.

He fashioned a crude printing press and a lead syllabic typeset, and in the early months of 1841, he printed the Cree hymnal.

It was a watershed moment for Indigenous language in North America. The Cherokee leader Sequoyah had already invented the Cherokee writing system in the 1820s. It spread rapidly and by 1830, a bilingual newspaper printed in Cherokee syllabics and English script was in circulation.

As with the Cherokee writing system among the Cherokee, the syllabic writing system spread among the Cree. Some scholars say Cree literacy rates exceeded the literacy rate of English and French settlers, and brought about what one researcher described as “near universal literacy.”

Other Indigenous communities across Canada and the far North quickly adopted the syllabics as their own.

According to the 2016 census, 96,575 people reported speaking Cree in Canada. Inuktitut claims another 40,000 or so speakers among Inuit. There was a time when syllabics were the main writing systems for both languages.

‘Great Canadian myth’

But where did the syllabics come from?

One Cree narrative credits a Wood Cree from the Stanley Mission area of what is now Saskatchewan. Mistanâkôwêw, or Calling Badger, is said to have delivered the syllabary to the Cree at least a decade before Evans published the Cree hymnal.

Winona Wheeler, associate professor of Indigenous studies at the University of Saskatchewan and a member of the Fisher River Cree Nation in Treaty 5 territory, said the Calling Badger narrative is well-known among Cree.

“To my people it's a sacred story on how syllabics were gifted to the people and the purposes that it was given for, and that [story] comes down through oral tradition,” Wheeler said.

Wheeler's paper, published 20 years ago — "Calling Badger and the Symbols of the Spirit Language: The Cree Origins of the Syllabic System" — is a spirited and sustained argument against the idea that Evans gave the Cree the written form of their own language.

“In all the oral accounts of the origins of the Cree syllabary it was told that the missionaries learned Cree syllabics from the Cree,” she wrote in that paper.

Wheeler describes the idea that Evans invented the syllabics as a “great Canadian myth.” The myth endured, Wheeler wrote, because “few question colonialist/conqueror renditions of the past and even fewer bothered asking Cree people directly about the origins of their writing system.”

“It depends on whose perspective you're looking at,” Wheeler said in a phone conversation.

“According to Western mythology and missionaries, it was a missionary who developed the Cree syllabic system,” she said.

“It depends on whose story you’re willing to listen to. But to my people it's a sacred story on how syllabics were gifted to the people and the purposes that it was given for.

“And that comes down through oral tradition.”

Calling Badger

Wes Fineday of the Sweetgrass First Nation in Saskatchewan is a keeper of the Calling Badger story, one of two Cree narratives on the origin of the syllabics.

Fineday’s great-grandfather on his mother’s side was Old Chief Fine Day, who learned the Calling Badger story from Strikes-Him-On-the-Back, who learned the story directly from Mistanâkôwêw — Calling Badger himself.

Fineday learned the story from his father, and he repeated the story of Calling Badger and the origin of the Cree syllabics for CBC Radio in two interviews in 1994 and 1998.

One day in or around 1830 in the Stanley Mission area of Saskatchewan, Calling Badger went into a period of extended seclusion. He was later found and thought to be dead.

He was laid out for a customary wake, but later woke up as if from a deep sleep.

Calling Badger said he was not dead, but in a state of altered consciousness in which he was in contact with the spirit world or what Fineday called “the fourth world.” When he returned, he was said to have brought with him a birch-bark scroll on which the syllabics were written.

“It’s a system of writing that was given to us by the spirit world so that we could begin to write down our language and the words in our language,” Fineday told CBC Radio at the time.

Calling Badger is said to have learned many other things while in the spirit world, including that his story would be forgotten for a time as people came from far away to populate the land.

I asked Fineday in a telephone conversation if the Calling Badger story was to be understood metaphorically or literally, but he declined to go into new detail for this story. He cited protocols that would first need to be followed.

In his previous recordings with CBC, he said, “The sacred stories … are not designed necessarily to provide answers but merely to begin to point out directions that can be taken.”

“Understand that it is not the work of storytellers to bring answers to you,” he said.

“What we can do is we can tell you stories and if you listen to those stories in the sacred manner with an open heart, an open mind, open eyes and open ears, those stories will speak to you.”

Listen to Wes Fineday speak to CBC Radio in 1998.

The mystical and the mundane

Wheeler said the mystical and the mundane were, and remain, intertwined for many Indigenous people.

“A lot of people get hung up on that and … they can't kind of wrap their heads around it,” she said. “But the reality is ... the mystical and the sacred was a part of everyday life.”

Wheeler would not speculate on the intended literalness of the Calling Badger narrative, but she said that for the elders, it is true.

“If that's what they say happened, then that's how they understood it to happen. And that's what they believed happened. I am not one to question that,” she said.

“The reality is that people received the syllabic system as spirit language. It was a gift from spirit. So naturally that required a spiritual kind of journey or a spiritual kind of relationship for that transmission to happen. It was a really powerful gift, and powerful gifts are gifts from spirit.”

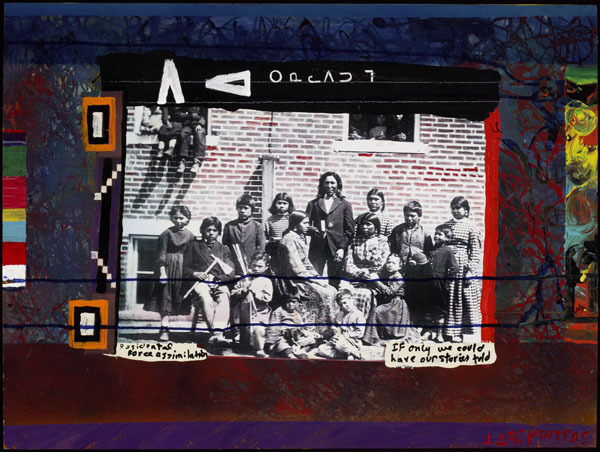

But Wheeler did question why the Cree origin narrative would be rejected because of its spiritual underpinnings, when the standard origin story that credits Evans carries its own kind of spirituality: it enshrines the idea that white evangelical Christian missionaries spread literacy among a supposedly illiterate Indigenous population, incapable of having developed a written form of their own language.

What we don’t know

Nobody knows exactly what happened in Norway House in the months Evans spent there with his Indigenous colleagues.

Whatever happened between Evans and his translators in conversation behind closed doors is central to the Cree syllabics origin story, and those doors remain closed.

What we do know is that out of their time together in Norway House — whatever that amounted to — came the first booklet printed in Cree syllabics.

Among those who likely would have known were the Ojibwe linguists Peter Jacobs (OJ Pahtahsega) and Henry Bird Steinhauer (Sowengisik) — who went with Evans to Norway House — as well as the Cree language experts John Sinclair and Sophie Mason, who joined the enterprise.

But no one with first-hand knowledge appears to have claimed authorship of the system, or to have said Evans invented it.

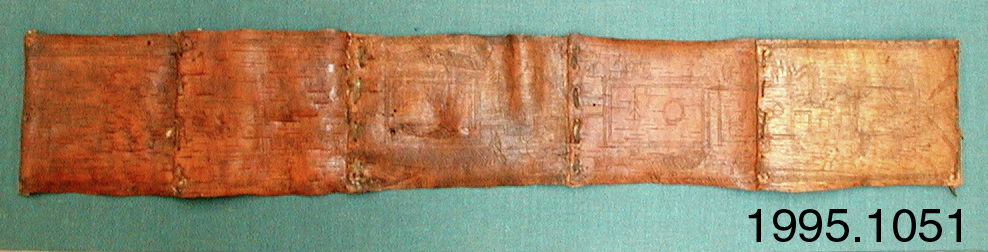

Although no birch-bark scroll with the syllabics inscribed on it that predates Norway House is known to exist, birch-bark inscriptions are far from unprecedented.

Birch bark can be peeled into thin silky strips that have the feel of fine parchment or vellum. Indigenous North Americans have used birch-bark paper, stitched and rolled into scrolls, for at least 400 years. The craft, which predates contact with Europeans, is called wiigwaasabakoon in Anishinaabe.

Scholars have noted that the Cree would likely have been, at the very least, familiar with Midewiwin religious practice that used inscribed birch-bark scrolls to preserve sacred stories and knowledge.

Inscribed birch-bark scrolls were in circulation long before Evans came along, but if Calling Badger’s birch-bark scroll with the syllabics inscribed on it survived, it’s not public knowledge.

For some, the absence of physical evidence makes the Cree origin narrative too convenient: that a story of the invention of the syllabary by the Cree — which includes a warning that foreigners would take credit — would be back-dated to shortly before Evans arrived, is taken as evidence of the Cree trying to subsume the invention of the syllabics into their own oral history.

Wheeler said she’s not aware of any surviving evidence of Cree syllabics pre-existing Norway House, but this doesn’t surprise her.

“Things weren't intended to last a long time. Unlike the Western world view, there was no priority given to posterity,” she said. “It wouldn't have been perceived a need to leave something written for the future because there was still so much power in oral transmission, and that was the primary form of communication.”

“I believe that's why syllabics or the written system did not take precedence over the verbal.”

Other evidence of Cree syllabics pre-existing Norway House may have also existed in the art and beadwork of the time, according to some scholars. Other commentators say the Cree may have kept their writing secret and well-guarded in light of colonial aggression.

Or else the syllabics may have existed before, but gained a resurgence after the Cree saw how important the written word was to French and English traders and bookkeepers. The Cree had, after all, been trading and socializing with them for more than 200 years before the syllabic hymnal was printed.

Listen to Winona Wheeler speak with the CBC North's Lawrence Nayally.

‘Whitewash that history’

If proximity in time and space makes for simple answers to simple questions, the question of the origin of Cree syllabics shouldn’t be hard to sort out.

The appearance of Cree syllabics in print was relatively recent in terms of global language history. It followed quickly on the heels of the Cherokee writing system developed by Sequoyah, but the creation of the Cherokee system was well-documented in a form Western scholarship is comfortable with — that is to say, in writing.

The Cree story of the syllabics was not preserved in writing. It was preserved in oral tradition and sacred stories passed down from storyteller to storyteller according to protocols designed to preserve and protect the stories.

For Chris Harvey — a linguist, PhD candidate at the University of Toronto and community linguist at the Stockbridge Muncie First Nation in Wisconsin — in the absence of new physical evidence, the answer to the question of the origin of Cree syllabics boils down to who you want to believe.

But he does say the simple narrative of Evans inventing the syllabics likely ignores — at the very least — the contribution of the Cree and Ojibwe language experts and translators who joined Evans at Norway House.

According to Harvey, the mechanics of the Cree syllabic system and many of its characters are unique, despite some components of the system that appear to have been borrowed from shorthand writing systems that existed around the same time.

Thanks in part to Harvey’s published work, in 2018 the Canadian Encyclopedia updated its chapter on Cree syllabics to say they were devised, “probably in collaboration with Indigenous Cree-speaking people.”

But still, where did the unique symbols come from?

According to Harvey, barring the discovery of syllabic artifacts from prior to what he describes as the Norway House “committee,” the best answer to that question is that the syllabics were a collaboration between Indigenous-language experts and Evans.

“Who was the first person to sit down and invent it? At the moment, the earliest records we have of that," Harvey said, are Cree- and Ojibwe-language experts and English missionaries in Norway House.

“That can complement the oral history. It doesn’t have to be in conflict with it.

“[The] syllabics could very well have been an Indigenous invention that the missionaries put those shorthand marks to complement it,” he said.

“And that Indigenous system could have come up by Cree people seeing how the English and the French were writing, and came up with their own system to complement it or to suit their own needs.

“That's also entirely possible because that's happened around the world many, many times.”

Harvey said it’s a “red flag” when Indigenous narratives compete with Western narratives.

“In the middle of these two stories is a very Canadian story of a people from different nations coming together and coming up with something wonderful,” Harvey said.

“It’s also a Canadian tradition to then whitewash that history and ignore the fact that it was a collaboration, and give three cheers for James Evans for inventing syllabics.”